This is going to be one of the most difficult blog posts I’ve ever written. It also may end up being one of the longest, so I applaud any of you that stick around to the end. In many ways, I don’t know if much of what I have to say will be as meaningful to my audience as it might be. I have no “shock conclusions” to make, no counterintuitive insights. What I saw is largely what I expected to see, and yet it felt no less meaningful for being predictable. And there were definitely a lot of unexpected moments, to be sure.

I think one of the reasons this blog post feels so difficult to write is that I’m aware that, as with any written work, it needs a narrative structure. There should be a beginning, a middle, and an end. There should be conflict (OK, that one’s pretty easy). There should be a hero’s journey, a challenge to overcome, something to take away, something to learn. And I struggle here because, of course, real life doesn’t always give us these things packaged up as neatly as that. But I suppose the best place to start is with the air raid alerts.

Living in the capital city of a country at war has its disadvantages. One of them is that you can’t have peace. That might seem obvious, but the reality of it is jarring. My first experience of Ukraine was waking up on the sleeper train to Kyiv, putting away my belongings, and then having my cabin mate, a Ukrainian man named Roman who looked to be my age, ask me, in broken English, whether I was meeting anyone in Kyiv. When I said that I had an AirBnb, he shook his head. No, he said, that wouldn’t do, because, you see, there is an air raid. What, right now? I asked, and he said, with sad eyes, yes, right now.

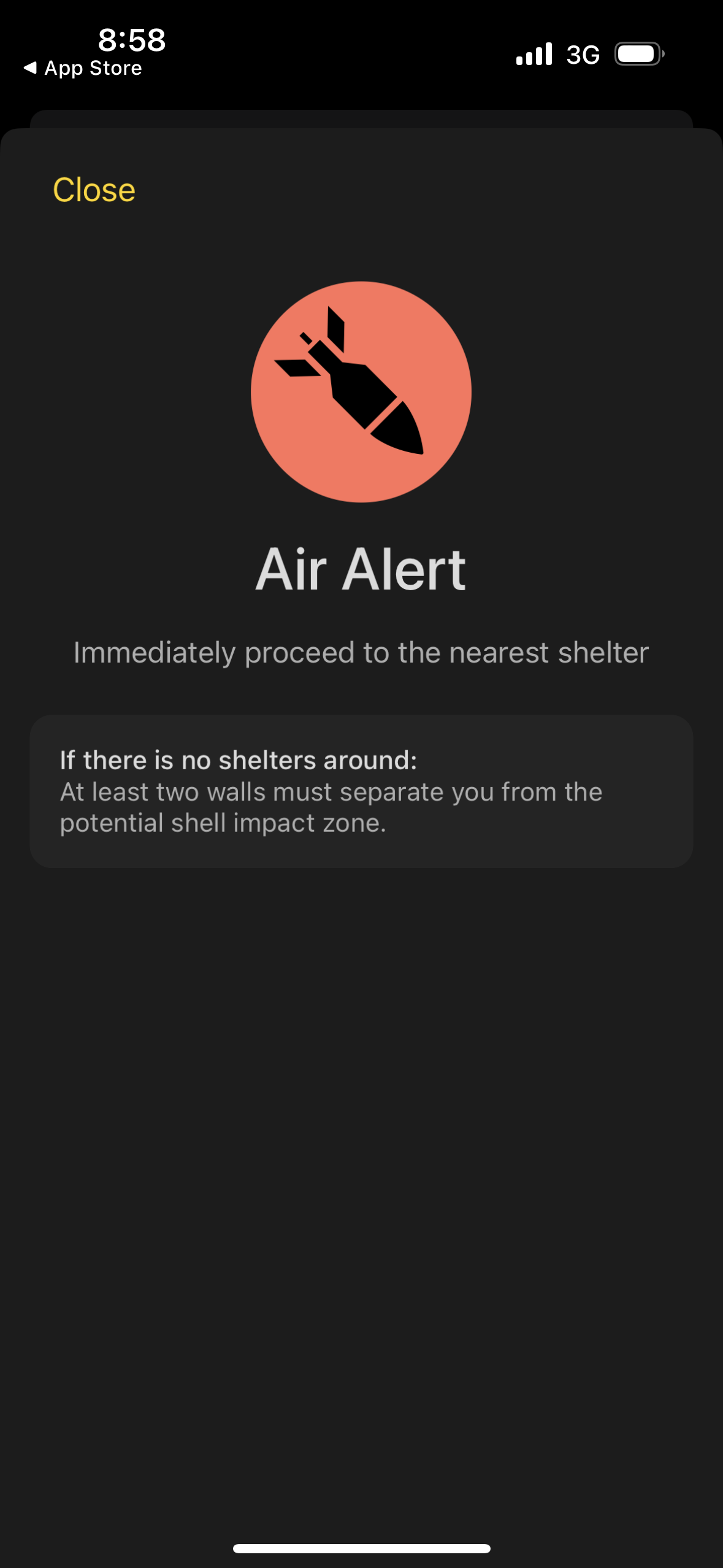

So that is how I ended up following a man I’d never met as we raced from the train terminal down into the Metro at Vokzalna, where I hastily met his brother and his family and we sat, deep in the tunnels, for the better part of 2 hours. He installed some apps on my phone that told me - in a voice both comforting and deeply jarring - when there was an air raid. I’ve heard that voice 2 more times since. He stood with his friends, talking in Ukrainian, while I sat, and stared at my phone (which didn’t work underground), and wondered - not for the first time - what I was doing there. It was scary for 10 minutes, and then, surprisingly, it was kind of boring.

But, eventually, as with all crises, that crisis ended. First Roman left - and yes, the air raid was still on, and this was my first lesson in Kyiv: life must go on. He was ready to go, and so off he went, with little more than a handshake, leaving me to wonder what the heck I was supposed to do. So I waited another 15 minutes, shrugged, and then I left, too. And just as I did, the air raid siren expired. I wondered: had anything been hit? (Answer: yes). Was the power out? (No.) Could I still get an Uber? (Yes.) My Uber driver asked me where I was from. When I told him, he laughed, and asked me if I worked for the CIA. I think he was kidding.

And so, an hour later, I was talking to Natalya, my AirBnb owner, a charming woman perhaps in her 60s of some sort of obvious Jewish descent, inside her tiny but warm flat somewhere near downtown Kyiv (don’t ask me to explain where it is). She asked me how the air raid went (Fine.). She asked me what I was doing here (I awkwardly explained my cover story about my ex-girlfriend and her sister). She talked to me about the war, and her Russian friend who said they “all had to be saved”, and how she heard the explosions this morning (even when they shoot down the missiles, they still have to land somewhere). She told me her daughter didn’t want to celebrate Christmas; it was too sad. Apparently 2 kids had been injured on a playground. She told me to take a shower while they still had water. I did.

And then, I went out. I had no idea where I was going. Truth be told, I had no idea what the heck I was doing here, and that was becoming painfully obvious. Nothing tourist-y would be open. The best I could do was walk, and so walk I did. I set my map for the Maidan, the square where the revolution happened. Over the next few hours I would walk 7 or 8 miles, visit an upscale shopping mall, sit and drink a Coke Zero on the Maidan, get scammed by a man who owned pigeons for $40, and generally experience life in Kyiv for the day. I tried (and failed) to get into St. Sophia. I ate at one of the open McDonalds (I had a Big Tasty, and it was both Big and Tasty). I stared at people and wondered what they were thinking. I felt wildly out of place. I walked along a pedestrian bridge next to the Dnipro. I started wearing my headphones because I didn’t want anyone to talk to me. I felt a profound sense of hope, and fear, and joy, and discomfort all at the same time. I stopped in a very nice shopping mall along the Maidan and I bought some things from a store called Made In Ukraine, where they had shirts that said Russian Warship, Go Fuck Yourself right next to dinner plates with traditional Ukrainian patterns. I stared at prices in Hryvnia and tried to figure out what the heck they meant before realizing, perhaps unsurprisingly, that everything was really, really cheap.

And I walked. I walked, and walked, and walked. I tried to visit several cathedrals, but nothing was open. I felt incredibly conspicuous, in my Stanley knit cap and my Fjallraven jacket and my extremely American face. Did they know I was from a country that wasn’t at war? Did they resent it? Were they happy I was here? Then I remembered the truth of the universe: nobody gives a shit. I took a deep breath (and then started coughing; I’m still sick). I walked up to the monument of the founding of Kyiv by Prince Volodomyr, but it - like many monuments - was covered in scaffolding. I saw a long display about the war, but it was all in Ukrainian, and I realized: this place is not for me. They do not care if I can read these signs. This is a private party. Yes, Kyiv wants you to know about itself, but that is not their priority right now. They are finding out about themselves. This is not a museum piece for international consumption. These people are busy; they are not here for me, or for you. Lead, follow, or get the heck out of the way.

At some point my subconscious processed the sound of a plane overhead, thinking that it was just commercial air traffic, until my thinking brain reminded me: there was no such thing. I looked up, suddenly frightened. Nobody else cared. I never could see what it was; too high, too cloudy.

Kyiv is a study in contrasts: it is alive, and modern, and fun. It is at war, it is mourning, it is depressed. It is cold, it is dark, it is scary. It is happy, it is ready for the future, it is in love. Your Apple Pay works (mostly), but all the museums are closed. You can go to McDonalds; at least, the three or four of them that reopened. The shops are open, but the escalators in the mall are turned off to save power. I walked past the tanks they have on display near the central square; burned out husks of Russian and civilian vehicles; you may have heard about them on the news. I started to take pictures and then I felt uncomfortable. There were, you see, no tourists. Everyone here is from here. Nobody is taking pictures. They already know what it means.

I came back, at around 5:30. It had gotten dark. I meant to write in my blog, maybe read a book. Instead, exhausted, I slept.

And then at 2 am I was awoken by another air raid. But that’s a story for the second blog post.